We are replacing the de facto protocol the internet has used for decades with QUIC, the latest and most radical step we’ve taken to optimize our network protocols to create a better experience for people on our services. Today, more than 75 percent of our internet traffic uses QUIC and HTTP/3 (we refer to QUIC and HTTP/3 together as QUIC). QUIC has shown significant improvements in several metrics, including request errors, tail latency, response header size, and numerous others that meaningfully affect the experience of people using our apps.

The Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) is currently developing both QUIC and HTTP/3 for standardization.

What are QUIC and HTTP/3?

Broadly speaking, QUIC is a replacement for the Transmission Control Protocol (TCP), one of the main protocols for internet communication. QUIC was originally developed internally by Google as Google QUIC, or gQUIC, and was presented to the IETF in 2015. Since then, it has been redesigned and improved by the broader IETF community, forming a new protocol we now call QUIC. HTTP/3 is the next iteration of HTTP, the standard protocol for web-based applications and servers. Together, QUIC and HTTP/3 represent the latest and greatest in internet-focused protocols, incorporating decades of best practices and lessons that we, Google, and the IETF community learned through running protocols on the internet.

QUIC and HTTP/3 generally outperform TCP and HTTP/2, which in turn outperform TCP and HTTP/1.1. TCP and HTTP/2 first introduced the concept of allowing a single network connection to support multiple data streams in a process called stream multiplexing. QUIC and HTTP/3 take this one step further by allowing streams to be truly independent by avoiding TCP’s dreaded head of line blocking, where lost packets jam and slow down all streams on a connection.

QUIC employs state-of-the-art loss recovery, which allows it to perform better than most TCP implementations under poor network conditions. TCP is also prone to ossification, where the protocol becomes difficult to upgrade because network middleboxes such as firewalls make assumptions about the packets’ format. QUIC avoids this issue by being fully encrypted, making protocol extensibility a first-class citizen and guaranteeing that future improvements can be made. QUIC also allows new ways to instrument, observe, and visualize transport behavior through QLOG, a JSON-based tracing format designed specifically for QUIC.

Experience-focused protocol development

We developed our own implementation of QUIC, called mvfst, in order to rapidly test and deploy QUIC on our own systems. We have a history of writing and deploying our own protocol implementations, first with our HTTP client/server library, Proxygen, and following that with the Zero protocol and then Fizz, our TLS 1.3 implementation. Facebook apps utilize both Fizz and Proxygen to communicate with our servers via Proxygen Mobile. We’ve also developed two security solutions for TLS, an extension called delegated credentials for securing certificates and DNS over TLS, for encrypting and authenticating web traffic over TLS.

Developing and deploying a new transport protocol from scratch

We wanted our new protocol to seamlessly integrate with our existing software and allow our developers to work quickly. As a proving ground, we decided to deploy QUIC on a large subset of Facebook network traffic, specifically internal network traffic that included proxied public traffic to Facebook. If QUIC didn’t work well for internal traffic, we knew it likely wouldn’t work well on the larger internet either.

In addition to shaking out bugs and other problematic behaviors, this strategy let us design a method that makes our network load balancer deeply QUIC-aware and maintains our load balancer’s zero-downtime release guarantees.

With this solid foundation in place, we moved toward deploying QUIC to people on the internet. Because of mvfst’s design, we were able to smoothly integrate QUIC support into Proxygen Mobile.

The Facebook app

The Facebook app was our first target for using QUIC on the internet. Facebook has a mature infrastructure that allows us to safely roll out changes to apps in a limited fashion before we release them to billions of people. We began with an experiment in which we enabled QUIC for dynamic GraphQL requests in the Facebook app. These are requests that do not have static content such as images and videos in the response.

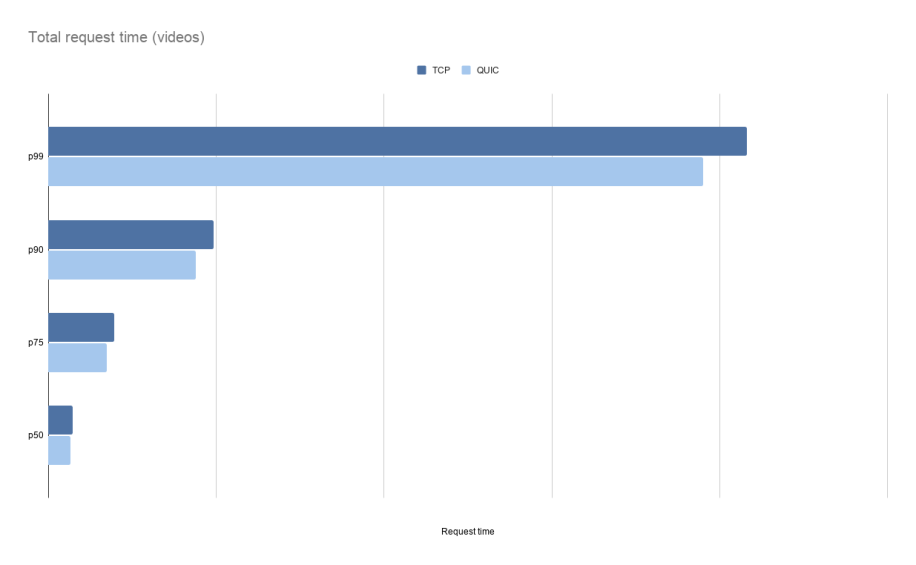

Our tests have shown that QUIC offers improvements on several metrics. People on Facebook experienced a 6 percent reduction in request errors, a 20 percent tail latency reduction, and a 5 percent reduction in response header size relative to HTTP/2. This had cascading effects on other metrics as well, indicating that peoples’ experience was greatly enhanced by QUIC.

However, there were regressions. What was most puzzling was that, despite QUIC being enabled only for dynamic requests, we observed increased error rates for static content downloaded with TCP. The root cause of this would be a common theme we’d run into when transitioning traffic to QUIC: App logic was changing the type and quantity of requests for certain types of content based on the speed and reliability of requests for other types of content. So improving one type of request may have had detrimental side effects for others.

For example, a heuristic that adapted how aggressively the app requested new static content from the server was tuned in a way that created issues with QUIC. When the app makes a request to, say, load the text content of a News Feed, it waits to see how long this request takes, then determines how many image/video requests to make from there. We found the heuristic was tuned with arbitrary thresholds, which probably worked OK for TCP. But when we switched to QUIC, these thresholds were inaccurate, and the app tried to request too much at once, ultimately causing News Feed to take longer to load.

Making it scale

The next step was to deploy QUIC for static content (e.g., images and videos) in the Facebook apps. Before doing this, however, we had to address two main concerns: the CPU efficiency of mvfst and the effectiveness of our primary congestion control implementation, BBR.

Up to this point, mvfst was designed to help developers move quickly and keep up with ever-changing drafts of QUIC. Dynamic requests, whose responses are relatively small compared with those of static requests, do not require significant CPU usage, nor do they put a congestion controller through its paces.

To address these concerns, we developed performance testing tools that allowed us to assess CPU usage and how effectively our congestion controller could utilize network resources. We used these tools and synthetic load tests of QUIC in our load balancer to make several improvements. One important area, for example, was optimizing how we pace UDP packets to allow for smoother data transmission. To improve CPU usage, we employed a number of techniques, including using generic segmentation offload (GSO) to efficiently send batches of UDP packets at once. We also optimized the data structures and algorithms that handle unacknowledged QUIC data.

QUIC for all content

Before turning on QUIC for all content in the Facebook app, we partnered with several stakeholders, including our video engineers. They have a deep understanding of the important product metrics and helped us analyze the experimental results in the Facebook app as we enabled QUIC.

The experiments showed that QUIC had a transformative effect on video metrics in the Facebook app. Mean time between rebuffering (MTBR), a measure of the time between buffering events, improved in aggregate by up to 22 percent, depending on the platform. The overall error count on video requests was reduced by 8 percent. The rate of video stalls was reduced by 20 percent. Several other metrics, including meta-metrics, considering a variety of factors and specifically outlier conditions, were significantly improved as well. QUIC improved the video viewing experience, with an outsized impact on networks with relatively poorer conditions, especially those in emerging markets.

But the path to these results came with roadblocks of its own. Similar to our experience with dynamic content, we encountered heuristics in the app that had been tuned to TCP’s behavior. For example, the apps on iOS and Android had differing mechanisms for estimating the available download bandwidth. These estimators sometimes overestimated the available bandwidth when using QUIC, causing the app to play a higher-quality video than the network could support and resulting in stalls.

We also had to tune and iterate the flow control parameters. Flow control limits the amount of data a receiver is willing to buffer from the sender. The Facebook app had a statically defined flow control limit for HTTP/2 that was implicitly tuned for TCP and did not perform well with QUIC. It took some experimental iteration for us to find the new optimal flow control value.

Instagram and beyond

QUIC’s performance on the Facebook app has been a testament to its ability to improve peoples’ experience on the internet, even on rich and complex applications like Facebook. In the future, we plan to continue to utilize more of QUIC’s existing features, such as connection migration and true 0-RTT connection establishment, as well as invest in improvements to congestion control and loss recovery.

We deployed QUIC to the Instagram apps as well, using the same strategies as our Facebook deployment — testing it on a small percentage of Instagram’s traffic and then scaling up. Today, QUIC is deployed on Instagram for iOS and Instagram for Android. Both versions of Instagram have seen metrics that are comparable to or better than those of the Facebook app. Facebook and Instagram on the web also have QUIC enabled, so as more web browsers enable support for QUIC, as Google has recently done for Chrome and Apple has done for Safari beta, even more people will benefit from the improvements. Beyond Instagram, we believe we can bring the benefits of QUIC to every experience in our family of apps, with QUIC eventually representing not just the majority but the entirety of Facebook’s internet traffic.

The IETF is on track to finalize the QUIC protocol as a request for comments (RFC) document sometime in 2021. Once this happens, even more websites, applications, and networking libraries will start offering QUIC for general use. In the very near future, new protocols like QUIC will be essential to unlocking innovative internet applications. For us, QUIC is a starting point from which we can continue to enhance people’s Facebook experience.

There are so many people within and outside of Facebook who have made this deployment possible. We would like to thank everyone who has participated in the IETF QUIC working group over the past several years, tirelessly debating and designing QUIC. The working group comprises a multitude of individuals from many different backgrounds who have produced a truly remarkable protocol in a relatively short period of time.