Understanding the text that appears on images is important for improving experiences, such as a more relevant photo search or the incorporation of text into screen readers that make Facebook more accessible for the visually impaired. Understanding text in images along with the context in which it appears also helps our systems proactively identify inappropriate or harmful content and keep our community safe.

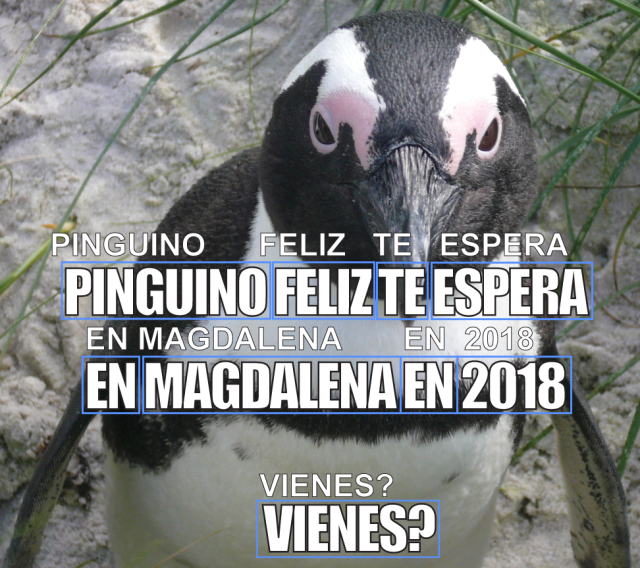

A significant number of the photos shared on Facebook and Instagram contain text in various forms. It might be overlaid on an image in a meme, or inlaid in a photo of a storefront, street sign, or restaurant menu. Taking into account the sheer volume of photos shared each day on Facebook and Instagram, the number of languages supported on our global platform, and the variations of the text, the problem of understanding text in images is quite different from those solved by traditional optical character recognition (OCR) systems, which recognize the characters but don’t understand the context of the associated image.

To address our specific needs, we built and deployed a large-scale machine learning system named Rosetta. It extracts text from more than a billion public Facebook and Instagram images and video frames (in a wide variety of languages), daily and in real time, and inputs it into a text recognition model that has been trained on classifiers to understand the context of the text and the image together.

Text extraction model

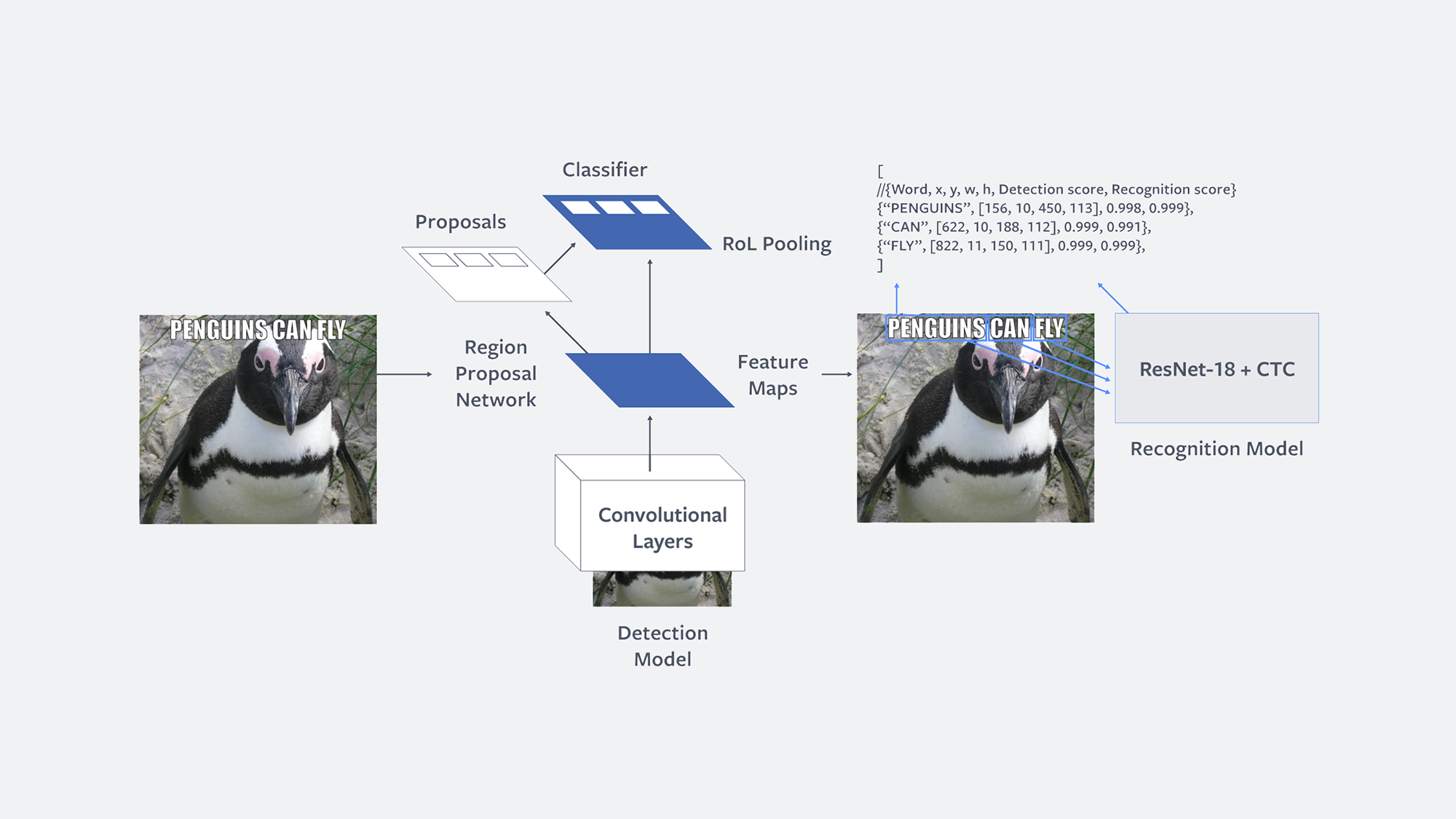

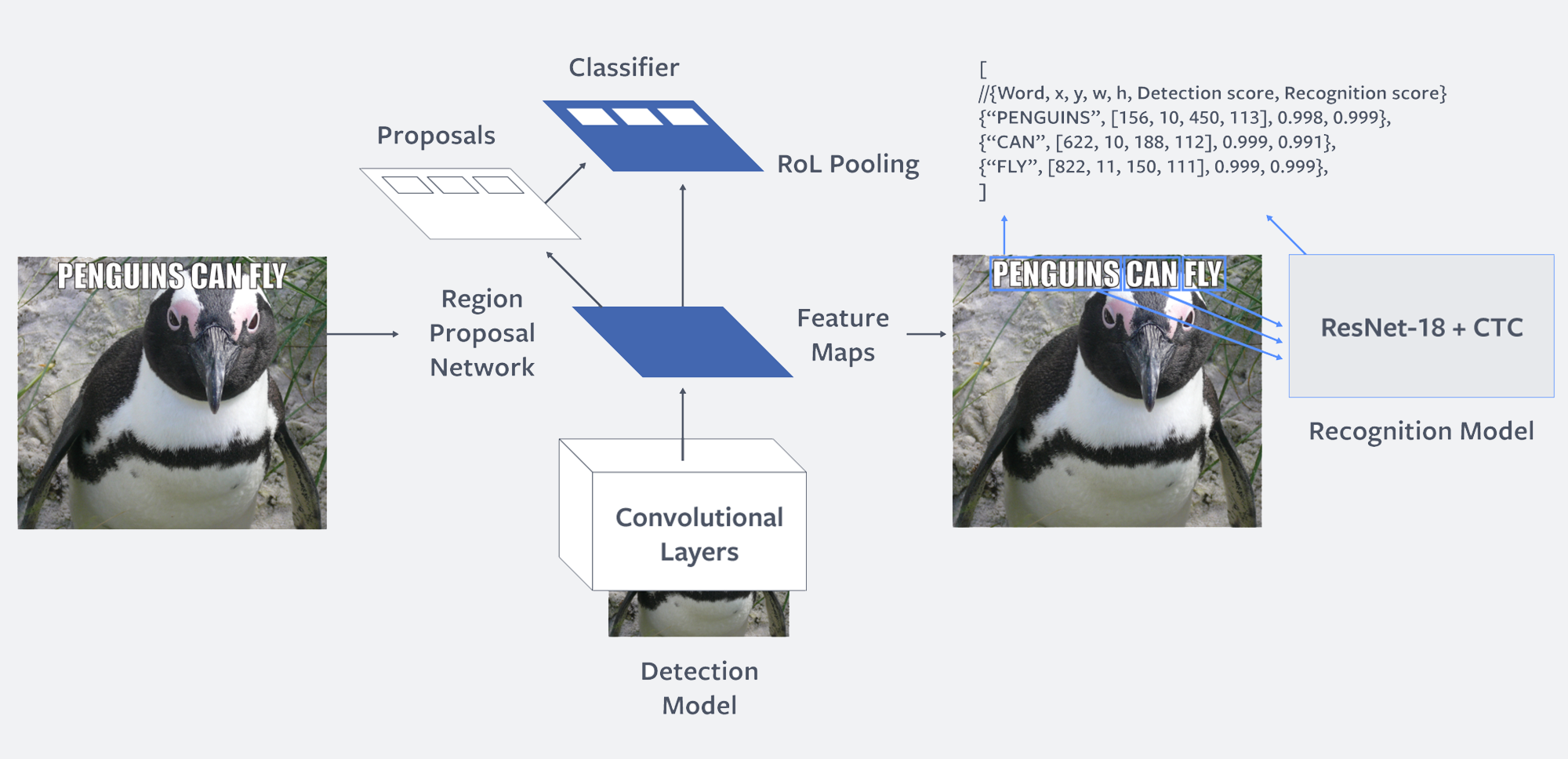

We perform text extraction on an image in two independent steps: detection and recognition. In the first step, we detect rectangular regions that potentially contain text. In the second step, we perform text recognition, where, for each of the detected regions, we use a convolutional neural network (CNN) to recognize and transcribe the word in the region.

For text detection, we adopted an approach based on Faster R-CNN, a state-of-the-art object detection network. In a nutshell, Faster R-CNN simultaneously performs detection and recognition by:

- Learning a CNN that can represent an image as a convolutional feature map.

- Learning a region proposal network (RPN), which takes that feature map as input and produces a set of proposed regions (or bounding boxes) that are likely to contain text, together with their confidence score.

- Extracting the features from the feature map associated with the spatial extent of each candidate box, and learning a classifier to recognize them (in our case, the categories are text and no text). The proposals are sorted by their confidence scores, and non-maximum suppression (NMS) is used to remove duplicates or overlaps and choose the most promising proposals. Additionally, bounding box regression is typically used to improve the accuracy of the produced regions by refining the proposals.

Figure: Two-step model architecture: The first step performs word detection based on Faster R-CNN. The second step performs word recognition using a fully convolutional model with CTC loss. The two models are trained independently.

The whole detection system (feature encoding, RPN, and classifiers) is trained jointly in a supervised, end-to-end manner. Our text detection model uses Faster R-CNN but replaces the ResNet convolutional body with a ShuffleNet-based architecture for efficiency reasons. ShuffleNet is significantly faster than ResNet and showed comparable accuracy on our data sets. We also modify the anchors in RPN to generate wider proposals, as text words are typically wider than the objects for which the RPN was designed. In particular, we use seven aspect ratios and five sizes, so the RPN generates 35 anchor boxes per region. To train the end-to-end detection system, we bootstrap the model with an in-house synthetic data set (more on that below) and then fine-tune it with human-annotated data sets so that it learns real-world characteristics. For training, we use the recently open-sourced Detectron framework powered by Caffe2.

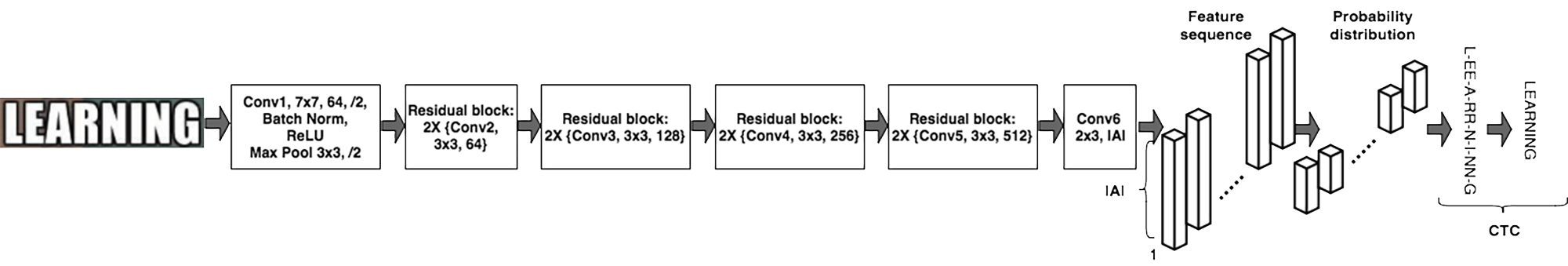

Our text recognition model is a CNN based on the ResNet18 architecture, as this architecture led to good accuracies while still being computationally efficient. To train our model, we cast it as a sequence prediction problem, where the input is the image containing the text to be recognized and the output is the sequence of characters in the word image. We use the connectionist temporal classification (CTC) loss to train our sequence model. Casting the problem as one of sequence prediction allows the system to recognize words of arbitrary length and to recognize out-of-vocabulary words (i.e., words that weren’t seen during training).

Preserving the spatial location of the characters in the image may not matter for other image classification problems, but it is very important for word recognition. Because of this, we make two modifications to the ResNet18 architecture:

- We remove the global average pooling layer at the end of the model and replace the fully connected layer with a convolutional layer that can accept inputs of different lengths.

- We reduce the stride of the last convolutional layers to better preserve the spatial resolution of the features.

Both changes help obtain good accuracies. Furthermore, we also use long short-term memory (LSTM) units to further improve the accuracy of our models.

Figure: Architecture of the text recognition model.

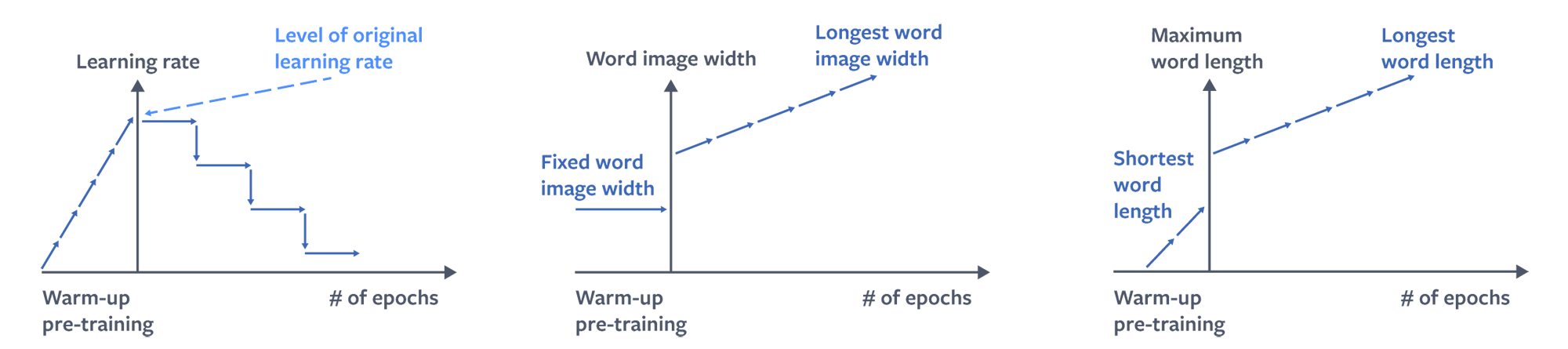

Training models with a sequence loss such as CTC is notably more difficult than training them with standard classification losses. For example, with a long word, one needs to predict all the characters of the word and in the right order, which is intuitively more difficult than just predicting a single label for an image. In practice, we observed that low learning rates led to underfit models, while higher learning rates led to model divergence. To address this problem, we draw inspiration from curriculum learning, where one first trains a model with a simple(r) task and increases the difficulty of the problem as training progresses. As a result, we modify our training procedure in two ways:

- We start training our model using only short words, with up to five characters. Once we have seen all the five-or-fewer-character words, we start training with words of six or fewer characters, then seven or fewer, etc. This significantly simplifies the problem.

- We use a learning rate scheduling, starting with a very low learning rate to ensure that the model doesn’t diverge, and progressively increase the learning rate during the first few epochs to ensure that the model reaches a good, stable point. Once we have reached this point, we start reducing the learning rate, as is standard practice when learning deep models.

Figure: Schematic visualization for the behavior of learning rate, image width, and maximum word length under curriculum learning for the CTC text recognition model.

Our model is not constrained to English text, and we currently support different languages and encodings such as, among others, Arabic and Hindi, in a unified model. Some of these present interesting technical challenges, such as right-to-left reading order or stacked characters.

To train a model that recognizes words in right-to-left order (when necessary) while still being able to recognize words in left-to-right order, we propose a very simple trick: We assume that words in, say, Arabic are actually read left to right, as with some other languages. Then, post-processing, we reverse the predicted characters as if they belonged to a language written right to left. This trick works surprisingly well, allowing us to have a unified model that works for both left-to-right and right-to-left languages.

Training data

Our approach for training data is a mixture of human-annotated public images with words and their locations as well as synthetic generation of text on public images. As we expand to more languages, manual annotation of images becomes increasing time-consuming. Moreover, the data distribution of textual images on Facebook and Instagram change quite rapidly and those who try to use text overlaid on images for spam or other inappropriate content continue to adapt their techniques. For these reasons, we chose to invest in a fast synthetic engine for dataset generation.

We draw inspiration from this method for our approach to synthetic engine for text extraction, which involves four steps:

- Sample data sources

- Understand scene layout via region segmentation and depth estimation

- Customize text styles

- Render and blend with Poisson image editing.

The original SynthText work was designed to mainly generate text-in-the-wild data with English text for research purposes. To adapt to the data distribution on Facebook, we make a few major modifications to the pipeline including making it Unicode compatible to support a wider variety of languages; incorporating special rules for languages such as Arabic (right to left), and Spanish and German (diacritics); and generating text in different forms and shapes to improve our text detection model to detect rotated text as well as learn affine transformations. For now, we also skip the scene understanding step, as we find that a significant number of the images we care about are meme-style overlaid text, although this hurts accuracy for scene-text.

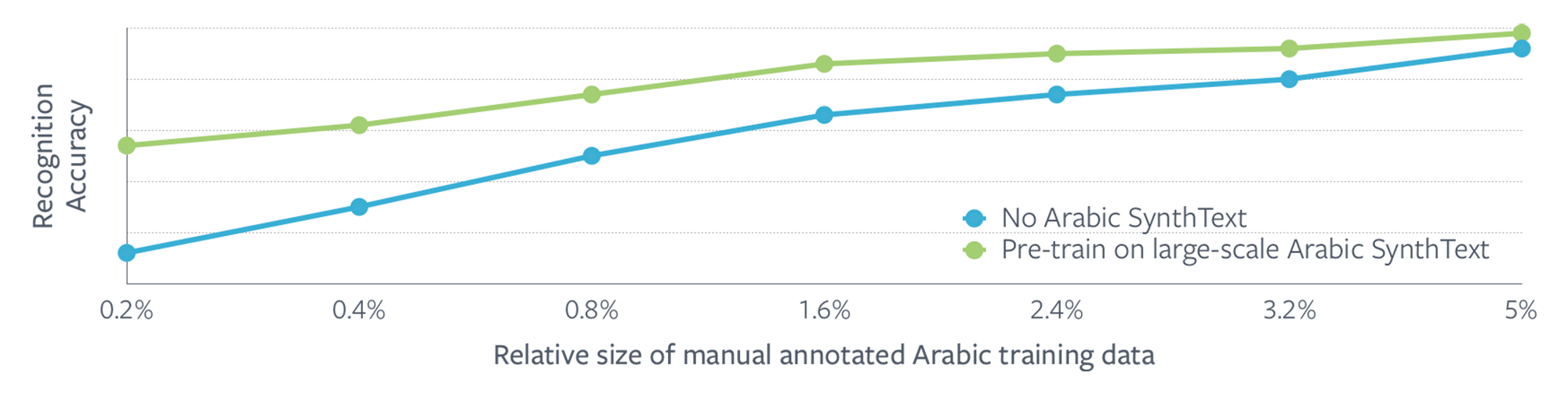

Our training approach involves first pre-training on SynthText and fine-tuning on human-annotated data, if available based on the language. Experiments and deployments for Arabic have demonstrated that pre-training on SynthText data can bring significant accuracy improvements when manual annotations are limited, and this diminishes with more manual data. The engine is allowing us to scale to many more languages without the traditionally challenging manual data-labeling hurdles.

Figure: Change in text recognition model accuracy with and without SynthText pre-training as a function of relative size of manually annotated data.

Inference

During inference, our models are run using Caffe2 on CPU machines with a batch size of 1, owing to real-time latency constraints. As a first-level filter, we apply a simple image classification model on public images to obtain the probability of text being present on the image. Images that cross a threshold are then fed into the text detection and recognition models sequentially.

Unlike image classification models, which work fairly well on low-resolution images, object detection models typically require higher-resolution images to more accurately perform bounding box regression. For our scenarios, we resize images such that the maximum dimension is 800 pixels while maintaining the aspect ratio. We found that the larger activation maps produced by the text detection model created a bottleneck. In addition to clogging the entire system memory I/O bandwidth, it also left other resources, such as CPU, underutilized. To overcome this, we quantize the weights and activations of the text detection model to 8-bit integers instead of 32-bit float computations without significant loss of accuracy. In theory, this reduces the memory bandwidth requirement by 4x.

Once the detection model is trained, we linearly quantize the fp32 weights and activations to [0, 255] by computing a pair of (scale, offset) per tensor (weights or output activation features) such that:

real_value = scale * (quantized_value - offset)The fundamentals of linear quantization applied to neural networks are explained here. It’s important to note that 0 in fp32 must be mapped exactly to 0 in int8 without quantization error owing to the disproportional occurrence of 0 in activations and weights. When we first evaluated our quantized model, we encountered a large drop in accuracy and we applied the following techniques to reduce the accuracy gap down to 0.2 percent:

- Net-aware quantization: We can often further reduce the range we’re quantizing for based on neighboring operators. For example, if an operator is only followed by ReLU, we can narrow down the range the output is quantized for by excluding negative values.

- L2 quantization error minimization: The default approach to choosing quantization params for a tensor is to sample the min/max values and map them to [0, 255] range linearly. Instead, generating a histogram of activation values per tensor and choosing the best range that minimizes the L2 quantization error provides a significant boost in accuracy. This squishes the range of tensor values (but with the constraint that the range spans 0) and makes the quantization procedure robust to outliers.

- Selective quantization: We find certain operators are highly sensitive to quantization error, such as the first convolutional layer of the network, and we avoid quantizing these.

For fast and efficient int8 inference we use FBGEMM, a highly optimized int8 GEMM library for AVX2/AVX512 servers, and a set of Caffe2 low-precision operators for x86 CPUs. Both are built by Facebook. We have implemented optimizations specific to our text detection model such as AVX2 kernels for 3×3 depth-wise convolution and ChannelShuffle operations used in ShuffleNet.

Once we obtain the bounding boxes for word locations on an image, they are cropped and resized to a height of 32 pixels with the aspect ratio maintained. All such crops for an image are batched into a single tensor with zero padding as needed and then processed at once by the text recognition model. We originally found that inference with single batches was bound on the memory I/O for reading weights owing to relatively smaller activation sizes, which could be amortized over all images in the batch. The trained PyTorch text recognition model is converted to Caffe2 using ONNX. We integrated Intel MKL-DNN into Caffe2 for acceleration on CPU.

Together with these techniques, we are able to process more than a billion public images per day through our system efficiently. The extracted text is used by downstream classifiers to immediately act upon policy-violating content or by product applications like photo search.

What lies ahead

Rosetta has been widely adopted by various products and teams within Facebook and Instagram. Text extracted from images is being used as a feature in various upstream machine learning models such as those to improve the relevance and quality of photo search, automatically identify content that violates our hate-speech policy on the platform in various languages, and improve the accuracy of classification of photos in News Feed to surface more personalized content.

But we are far from done. The rapid growth of videos as a way to share content, the need to support many more languages, and the increasing number of ways in which people share content make text extraction from images and videos an exciting challenge that helps push the frontiers of computer vision research and applications.

Text on images comes in a wide variety of forms with very little structure: simple horizontal overlaid text in memes; rotated, warped, obfuscated, or otherwise distorted text; or scene-text in photographs of storefronts or street signs. Moreover, the patterns of text on images on Facebook tend to change rapidly, making this an ongoing challenge. Motivated by Rotation Region Proposal Networks, we are working on extending Faster R-CNN with anchors of arbitrary rotations, as well as experimenting with Spatial Transformer Networks to learn and correct for arbitrary affine transformations between the detection and recognition stages.

As we look beyond images, one of the biggest challenges is extracting text efficiently from videos. The naive approach of applying image-based text extraction to every single video frame is not scalable, because of the massive growth of videos on the platform, and would only lead to wasted computational resources. Recently, 3D convolutions have been gaining wide adoption given their ability to model temporal domain in addition to spatial domain. We are beginning to explore ways to apply 3D convolutions for smarter selection of video frames of interest for text extraction.

Text recognition models studied in literature predominantly focus on English or Latin alphabet data sets. To support a global platform, we are also continuing to invest in extending the text recognition model for the wide number of languages used on Facebook. With a unified model for a large number of languages, we run the risk of being mediocre for each language, which makes the problem challenging. Moreover, it’s difficult to get human-annotated data for many of the languages. Although SynthText has been helpful as a way to bootstrap training, it’s not yet a replacement for human-annotated data sets. We are therefore exploring ways to bridge the domain gap between our synthetic engine and real-world distribution of text on images.

We would like to express our gratitude to our colleagues Guan Pang, Jing Huang, Vinaya Polamreddi, Boris Vassilev, Tyler Matthews, Mahalia Miller, and Fedor Borisyuk for their work on this research and on the resulting paper, presented at KDD 2018.