Over the past two years Facebook has been working with browser vendors to improve browser caching. As a result of this work, both Chrome and Firefox recently launched features that make their caches significantly more efficient both for us and for the entire web. These changes have helped reduce static resource requests to our servers by 60% and as a result have dramatically improved page load times. (A static resource is a file our server reads from disk and then just serves it without running any extra code.) In this post, we’ll detail the work we did with Chrome and Firefox to get this result — but let’s start with a a bit of context and definitions that help explain the problem that needed to get solved. Up first, revalidation.

Every revalidation means another request

As you navigate the web you often reuse the same resources — things like logos or JavaScript code that are reused across pages. It’s wasteful if browsers download these resources over and over again.

To stop unnecessary downloads, HTTP servers can specify an expiration time and a validator for each request that can indicate to a browser that it doesn’t need to download until later. An expiration time tells the browser how long it can re-use the latest response and is sent using the Cache-Control header. A validator is a way to allow the browser to continue to re-use the response even after the expiration time. It allows the browser to check with the server if a resource is still valid and re-use the response. Validators are sent via Last-Modified or Etag headers.

Here’s an example resource that expires in an hour and has a last-modified validator.

$ curl https://example.com/foo.png

> GET /foo.png

< 200 OK

< last-modified: Mon, 17 Oct 2016 00:00:00 GMT

< cache-control: max-age=3600

<image data>

In this example, for the next hour, a browser which received this response can re-use it without contacting example.com. After that the browser must revalidate the resource by sending a conditional request to check if the image is still up to date:

$ curl https://example.com/foo.png -H 'if-modified-since: Mon, 17 Oct 2016 00:00:00 GMT'

> GET /foo.png

> if-modified-since: Mon, 17 Oct 2016 00:00:00 GMT

If the image was not modified

< 304 Not Modified

< last-modified: Mon, 17 Oct 2016 00:00:00 GMT

< cache-control: max-age=3600

If the image was modified

< 200 OK

< last-modified: Tue, 18 Oct 2016 00:00:00 GMT

< cache-control: max-age=3600

<image data>

A not modified (304) response is sent if the resource has not been modified. This has benefits over downloading the whole resource again, as much less data needs to be transferred, but it doesn’t eliminate the latency of the browser talking to the server. Every time a not-modified response is sent, the browser already had the correct resource. We want to avoid these wasted revalidation by allowing the client to cache for longer.

Signaling no download needed over the long term

Revalidation raises a difficult question: How long should your expiration times be? If you send expiration times of one hour, browsers will have to talk to your server to check if your resources have been modified every hour. Many resources like logos or even JavaScript code change rarely; every hour is overdoing it in those cases. On the other hand, if your expiration times are long, browsers will serve the resource from cache potentially showing users out of date resources.

To solve this problem, Facebook uses the concept of content addressed URLs. Rather than our URLs describing a logical resources (“logo.png,” “library.js”) our URLs are a hash of our content. Every time we release our site, we take each static resource and hash it. We maintain a database that stores those hashes and maps them to their contents. When serving a resource rather than serving it by name, we create a URL that has the hash. For example, if the hash of logo.png is abc123, we use the URL http://www.facebook.com/rsrc.php/abc123.png.

Because this scheme uses the hash of the contents of a file as the URL, it provides an important guarantee: The contents of a content addressed URL never change. Therefore we serve all of our content addressed URLs with a long expiration time (currently one year). Additionally, because the contents of our URLs never change, our servers will always respond with a 304 not-modified response for any and all conditional requests for static resources. This saves on CPU cycles and lets us respond to such requests quicker.

The problem with reloads

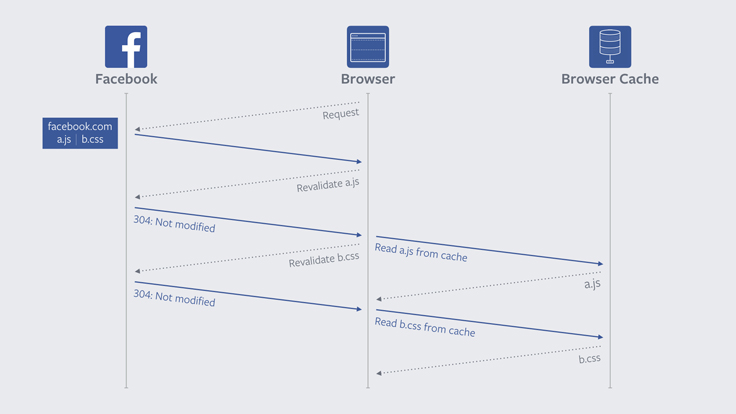

The browser’s reload button exists to allow the user to get an updated version of the current page. In order to meet this goal, when you reload, browsers revalidate the page that you are currently on, even if that page hasn’t expired yet. However, they also go a step further and revalidate all sub-resources on the page — things like images and JavaScript files.

This revalidation of subresources means that even if a user has already visited the site that they are reloading, every subresource must make a round-trip to the server. On sites that use content addressed URLs, like Facebook, these revalidation requests are futile. The contents of content addressed URLs never change, so revalidations always result in a 304 Not Modified. In other words, the revalidation, the request and the resources spent on the whole process were never necessary in the first place.

Too many conditional requests

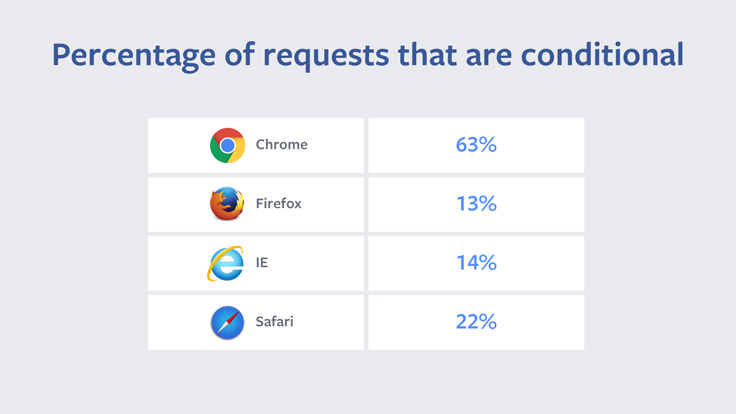

In 2014 we found that 60% of requests for static resources resulted in a 304. Since content addressed URLs never change, this means there was an opportunity to optimize away 60% of static resource requests. Using Scuba we started exploring data around conditional requests. We noticed that there were substantial differences between the performance of different browsers.

Seeing as Chrome had the most 304s, we started working with them to see if we could figure why they were sending such a higher percentage of conditional requests.

Chrome

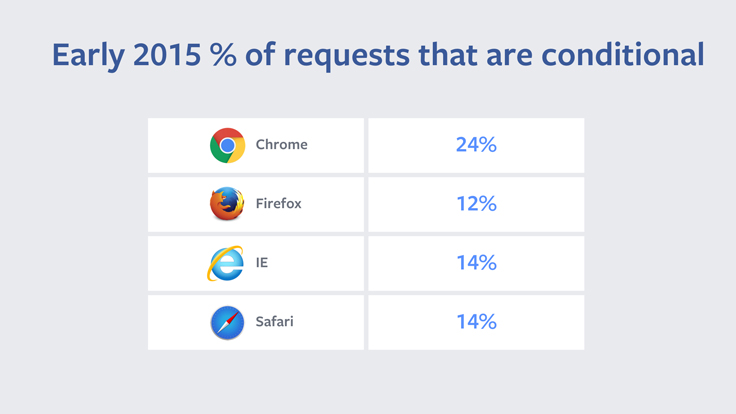

A piece of code in Chrome hinted at the answer to our question. This line of code listed a few reasons, including reload, for why Chrome might ask to revalidate resources on a page. For example, we found that Chrome would revalidate all resources on pages that were loaded from making a POST request. The Chrome team told us the rationale for this was that POST requests tend to be pages that make a change — like making a purchase or sending an email — and that the user would want to have the most up-to-date page. However, sites like Facebook use POST requests as part of our login process. Every time a user logged in to Facebook the browser ignored its cache and revalidated all the previously downloaded resources. We worked with Chrome product managers and engineers and determined that this behavior was unique to Chrome and unnecessary. After fixing this, Chrome went from having 63% of its requests being conditional to 24% of them being conditional.

Our work with Chrome on the login issue is a great example of Facebook and browsers working together to quickly squash a bug. In general, when we look at data, we often break it up on a per-browser level. If we find that one browser is an outlier, it’s an indication that something in the browser can be optimized. We can then work with the browser vendor to solve the issue.

The fact that the percentage of conditional requests from Chrome was still higher than other browsers seemed to indicate that we still had some opportunity here. We started looking into reloads and discovered that Chrome was treating same URL navigations as reloads while other browsers weren’t. A same URL navigation is when a user is on a page and then tries to load to the same page via the navigation bar. Chrome fixed the same URL behavior, but we didn’t see a huge metric change. We began to discuss changing the behavior of the reload button with the Chrome team.

Changing the revalidation behavior of the reload button is a change to a long standing design on the web. However, as we discussed the issue we realized that it was unlikely developers were relying on this behavior. End-users of websites don’t know about expiration times and conditional requests. While some users might press the reload button when they want a more up to date version of their page, Facebook’s statistics showed that the majority of users do not use the reload button. Therefore, if a developer is changing a resource that currently has an expiration time of X, the developer must either be willing to have users have stale data until that time or they must change the URL. If developers are already doing this, then there is no reason to revalidate subresources.

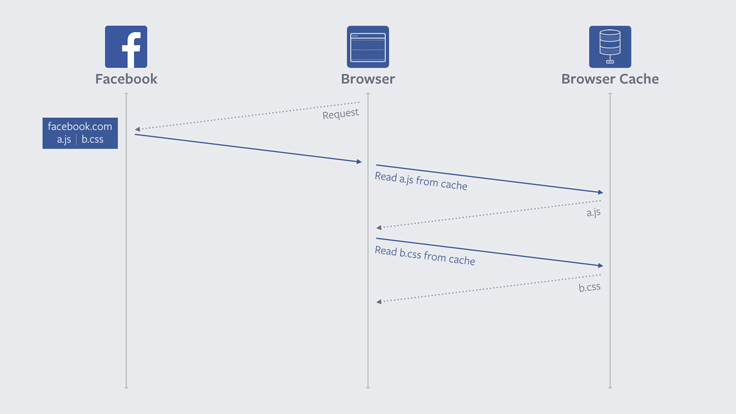

There was some debate about what to do, and we proposed a compromise where resources with a long max-age would never get revalidated, but that for resources with a shorter max-age the old behavior would apply. The Chrome team thought about this and decided to apply the change for all cached resources, not just the long-lived ones. You can read more about their process here. Because of Chrome’s blanket approach, all developers and sites are able to see improvement without making any changes themselves.

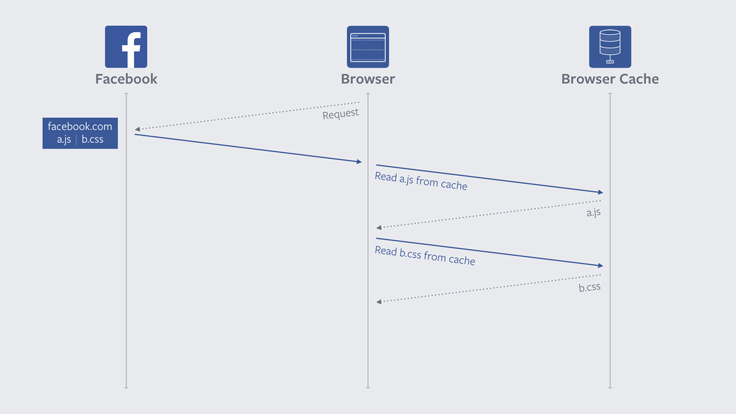

In this illustration we can see that unlike earlier, where a network request was needed for each subresource on the reloaded page, this time we can just read each file directly from cache without being blocked on the network.

After Chrome launched this final change the percent of Chrome conditional requests dropped dramatically — a win both for our servers, which sent fewer Not Modified requests and for users, who were able to more quickly reload Facebook.

Firefox

Once Chrome settled on a fix, we started engaging other browser vendors about the reload button behavior. We filed a bug with Firefox and they chose not to alter the long standing behavior of the reload button. Instead, Firefox implemented a proposal from one of our engineers to add a new cache-control header for some resources in order to tell the browser that this resource should never be revalidated. The idea behind this header is that it’s an extra promise from the developer to the browser that this resource will never change during its max-age lifetime. Firefox chose to implement this directive in the form of a cache-control: immutable header.

With this added header a request for a resource to Facebook would now return something like:

$ curl https://example.com/foo.png

> GET /foo.png

< 200 OK

< last-modified: Mon, 17 Oct 2016 00:00:00 GMT

< cache-control: max-age=3600, immutable

<image data>

Firefox was quick in implementing the cache-control: immutable change and rolled it out just around when Chrome was fully launching their final fixes to reload. You can read more about Firefox’s changes here.

There is a bit more developer overhead for Firefox’s change, but after we modified our servers to add the immutable header we began to see some great results.

After the fix

Chrome and Firefox’s measures have effectively eliminated revalidation requests to us from modern version of those browsers. This reduces traffic to our servers, but more importantly improves load time for people visiting Facebook.

Unfortunately, this change was the type that is difficult to measure the exact improvements — newer versions of browsers contain so many changes that it is nearly impossible to isolate the impact of a specific change. However, in testing this change the Chrome team was able to run an A/B test that found for mobile users with a 3G connection across all websites the 90th percentile reload was 1.6 seconds faster with this change.

Conclusion

This was a tricky issue because we were asking to modify long-standing web behavior. It highlights how web browsers can, and do, work with web developers to make the web better for everyone. We’re happy to have such a good working relationship with our friends on the Chrome and Firefox teams, and are excited about our continuing collaborations to improve the web for everyone.