Timeline isn’t just a bold new look for Facebook—it’s also the product of a remarkably ambitious engineering effort. While our earlier profile pages surfaced a few days or weeks of activity, from the onset we knew that with Timeline we had to think in terms of years and even decades. At a high level we needed to scan, aggregate, and rank posts, shares, photos and check-ins to surface the most significant events over years of Facebook activity.

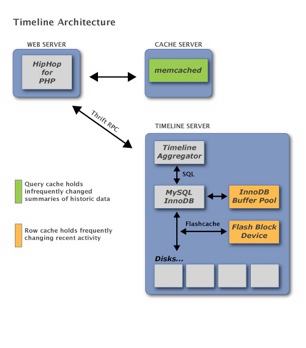

The schedule for Timeline was very aggressive. When we sat down to build the system, one of our key priorities was eliminating technical risk by keeping the system as simple as possible and relying on internally-proven technologies. After a few discussions we decided to build on four of our core technologies: MySQL/InnoDB for storage and replication, Multifeed (the technology that powers News Feed) for ranking, Thrift for communications, and memcached for caching. We chose well-understood technologies so we could better predict capacity needs and rely on our existing monitoring and operational tool kits.

Denormalizing the data

Before we began Timeline, our existing data was highly normalized, which required many round trips to the databases. Because of this, we relied on caching to keep everything fast. When data wasn’t found in cache, it was unlikely to be clustered together on disk, which led to lots of potentially slow, random disk IO. To support our ranking model for Timeline, we would have had to keep the entire data set in cache, including low-value data that wasn’t displayed.

A massive denormalization process was required to ensure all the data necessary for ranking was available in a small number of IO-efficient database requests

Once denormalized, each row in the database contained both information about the action and enough ranking metadata so it could be selected or discarded without additional data fetches. Data is now sorted by (user, time) on disk and InnoDB does a great job of streaming data from disk with a primary key range query.

Some of our specific challenges of the denormalization process were:

- Dozens of legacy data formats that evolved over years. Peter Ondruška, a Facebook summer intern, defined a custom language to concisely express our data format conversion rules and wrote a compiler to turn this into runnable PHP. Three “data archeologists” wrote the conversion rules.

- Non-recent activity data had been moved to slow network storage. We hacked a read-only build of MySQL and deployed hundreds of servers to exert maximum IO pressure and copy this data out in weeks instead of months.

- Massive join queries that did tons of random IO. We consolidated join tables into a tier of flash-only databases. Traditionally PHP can perform database queries on only one server at a time, so we wrote a parallelizing query proxy that allowed us to query the entire join tier in parallel.

- Future-proofing the data schema. We adopted a data model that’s compatible with Multifeed. It’s more flexible and provides more semantic context around data with the added benefit of allowing more code reuse.

Timeline aggregator

We built the Timeline aggregator on top of the database. It started its life as a modified version of the Multifeed Aggregator that powers News Feed, but now it runs locally on each database box, allowing us to max out the disks without sending any data over the network that won’t be displayed on the page.

The aggregator provides a set of story generators that handle everything from geographically clustering nearby check-ins to ranking status updates. These generators are implemented in C++ and can run all these analyses in a few milliseconds, much faster than PHP could. Much of the generator logic is decomposed into a sequence of simple operations that can be reused to write new generators with minimal effort.

Caching is an important part of any Facebook project. One of the nice properties of Timeline is that the results of big queries, such as ranking all your activity in 2010, are small and can be cached for a long period without cache invalidations. A query result cache is of huge benefit and memcached is an excellent solution.

Recent Activity changes frequently so a query cache is frequently invalidated, but regenerating the summary of Recent Activity is quite fast. Here a row cache helps further boost query performance. We rely on the InnoDB buffer pool in RAM and our own Flashcache kernel driver to expand the OS cache onto a flash device.

Developing in parallel

Timeline started as a Hackathon project in late 2010 with two full-time engineers, an engineering intern, and a designer building a working demo in a single night. The full team ramped up in early 2011, and the development team was split into design, front-end engineering, infrastructure engineering, and data migrations. By doing staged and layered prototyping, we achieved an amazing amount of development parallelism and rarely was any part of the team blocked by another. Early on in the project we were simultaneously:

- Designing UI prototypes with our pre-existing but non-scalable backend,

- Building production frontend code on a simulation of the scalable backend,

- Building the scalable backend using samples of de-normalized data from a prototype of denormalization migration,

- Building the framework to run the full-scale denormalization process,

- Collecting and copying the data necessary for the denormalization,

- Performing simulated load testing to validate our capacity planning estimates.

In retrospect, that’s pretty crazy. We had to move a lot of mountains to go from the initial infrastructure review meeting to successfully turning on the 100% backend load test in just six months. Done another way, this project could have taken twice as long – and that’s being generous.

Timeline has been a wonderful opportunity to work closely with the product team. Our constant collaboration was critical to ensuring the infrastructure we built supported their product goals while simultaneously guiding the product toward features that we could implement efficiently.

As millions of users enable Timeline, it is wonderfully exciting to see all the positive feedback and even more exciting to see our performance graphs look just like our simulations.

Ryan Mack, an infrastructure engineer, looks forward to rediscovering this blog post on his timeline a decade from now.